“This history was totally hidden from white children. And that was deliberate.” from The Atlantic

I think that the Tulsa Race Massacre may have garnered a single sentence in my history book when I studied A.P. History in high school in Southern California. A single sentence or even paragraph isn’t enough to do it justice, especially if you look at race massacres in the United History as part of a broader phenomenon.

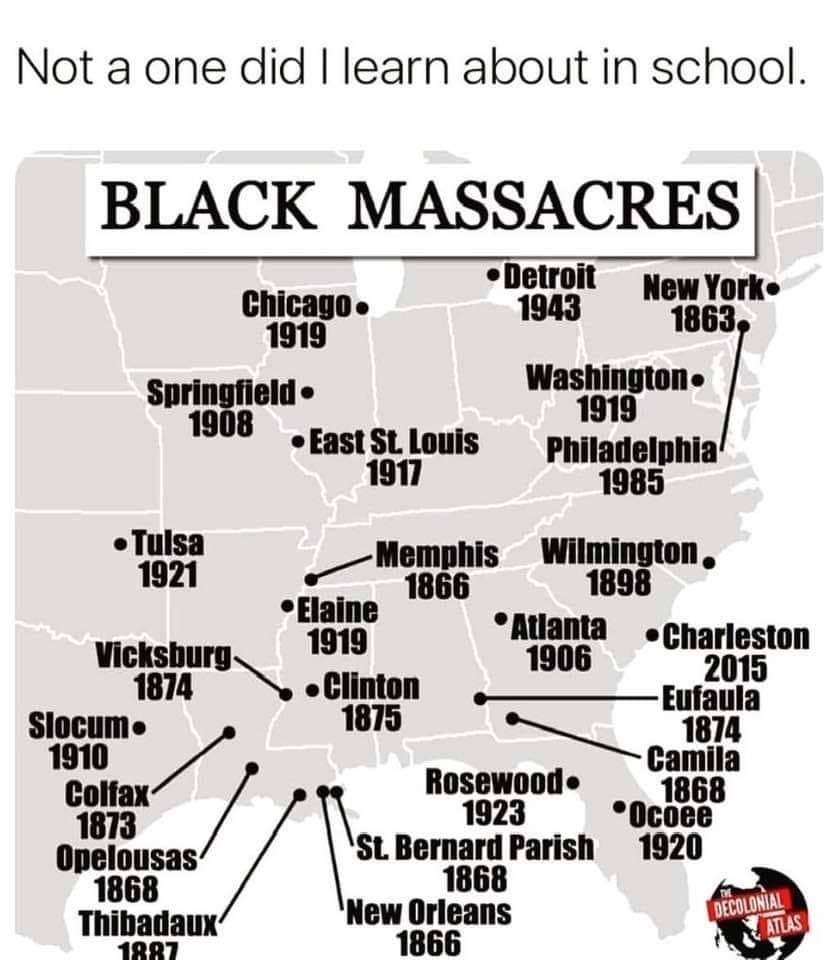

Only in searching out more information about the Tulsa Race Massacre, did I come across more incidents: The Wilmington Massacre of 1898 in North Carolina, the Elaine Massacre of 1919 in Arkansas, the Colfax Massacre of 1873 in Louisiana, the Rosewood Massacre of 1923 in Florida, the Hamburg Massacre of 1876 in South Carolina, and The Ocoee Massacre of 1920 in Florida. I am certain that I am missing many more. Please help me out by letting me know in the comments.

During these past four years, I have learned about “Karens” through the media. Karens often use their white privilege against people of color, particularly African Americans.

Karen is a pejorative term for a woman seeming to be entitled or demanding beyond the scope of what is normal. The term also refers to memes depicting white women who use their privilege to demand they get their way. from Wikipedia

But if you realize that Karens are not new. They have played a role throughout U.S. history. This gives these race massacres a new lens through which to view what happened. The Tulsa Race Massacre and its near-total erasure from U.S. history books also give context into current events happening all over the United States both to suppress the vote of Blacks and to rewrite history without racism.

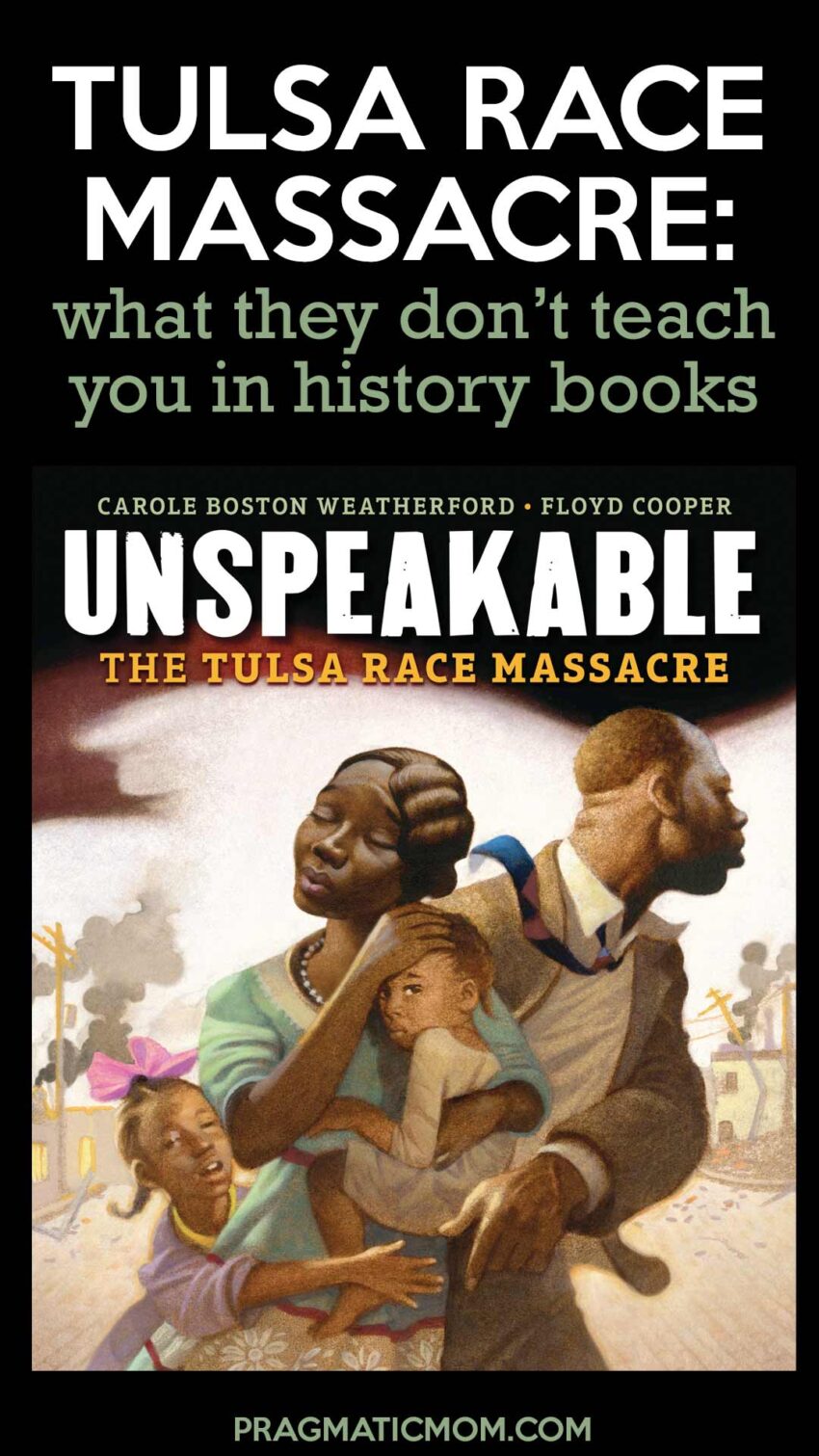

For those who want to learn more, I recommend starting with Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre by Carole Boston Weatherford. A single book can illuminate the way to a more accurate view of U.S. history.

The Tulsa Race Massacre: June 1, 1921

Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre by Carole Boston Weatherford, illustrated by Floyd Cooper

But in 1921, not everyone in Tulsa was pleased with these signs of Black wealth — undeniable proof that African Americans could achieve just as much, if not more than, whites…

Seventy-five years passed before lawmakers launched an investigation to uncover the painful truth about the worst racial attack in the United States history:

police and city officials had plotted with the white mob to destroy the nation’s wealthiest Black community.

This is a deeply personal book for both Carole Boston Weatherford and Floyd Cooper. Cooper’s grandfather grew up where the Tulsa Race Massacre occurred. Floyd has memories passed down from his grandfather of what happened during those two days when the one-mile stretch of Greenwood Avenue was destroyed. Weatherford also has personal connections to race lynchings.

Use this book to fill in the pivotal moments in history that are not being taught in our schools. For further insight, compare Durham, North Carolina, home to another Black Wall Street, with Greenwood Avenue in Tulsa. [picture book, ages 8 and up]

Viola Fletcher, who at 107 is the oldest living survivor of the 1921 Tulsa race massacre, testified Wednesday before a House subcommittee studying legal remedies to atone for the damage a violent mob did to a thriving Tulsa neighborhood then known as “Black Wall Street.” Watch her testimony.

The Wilmington Massacre of 1898

The Wilmington Massacre is widely acknowledged as a coup and as a foundational moment in creating a white supremacist state.

The Wilmington insurrection of 1898, also known as the Wilmington massacre of 1898 or the Wilmington coup of 1898, was a mass riot and insurrection carried out by white supremacists in Wilmington, North Carolina, United States, on Thursday, November 10, 1898. from Wikipedia

Conservatives in North Carolina don’t often bring up the Wilmington Massacre. Even many of those North Carolinians who are now aware of it are still reluctant to talk about it. Those who do sometimes stumble over words like insurrection and riot—loaded terms, and imprecise ones.

Not only was it a coup, though; the massacre was arguably the nadir of post-slavery racial politics…

“They burned down black newspapers all over the state,” Cecelski says. “They shut down entry to the city from blacks and Republicans … It’s important not to forget that this was a planned thing. This wasn’t two people getting in a fight in a street corner and sparking underlying racial tensions or something like that…”

Glenda Gilmore, a North Carolina native and a professor of history at Yale, refers to the whitewashed period as “a 50-year black hole of information.” According to Gilmore, the bloody history of white supremacy was largely unacknowledged in the state’s educational system. “Someone like me, I had never heard the word ‘lynching’ until I was 21,” she says. “This history was totally hidden from white children. And that was deliberate.”

Lost in the fire that destroyed The Daily Record were the lives of black citizens and the spirit of a thriving black community, and also the most promising effort in the South to build racial solidarity.

from The Atlantic

The Elaine Massacre: The bloodiest racial conflict in U.S. history (October 1, 1919)

“The Elaine massacre occurred on September 30–October 1, 1919, at Hoop Spur in the vicinity of Elaine in rural Phillips County, Arkansas. Some records of the time state that eleven black men and five white men were killed.”

from Wikipedia

The Ocoee Massacre: The Truth Laid Bare (November 2, 1920)

“In response to an attempt by African Americans to exercise their legal and democratic right to vote, at least 50 African Americans were murdered in a brutal massacre in Ocoee, Florida on Nov. 2, 1920 in what is now called the Ocoee Massacre.”

from The Zinn Project

Columbia Race Riot: February 25 to 28, 1946

“The race riot in Columbia, Tennessee, a town of 10,911, from February 25 to 28, 1946 was early example of post-World War II racial violence between African Americans and whites in the United States. On February 25, 1946, James Stephenson, a World War II veteran, and his mother, Gladys Stephenson, went to Castner-Knott, a local department store, to pick up the radio they had taken for repair, not knowing it had been sold to another customer. When Mrs. Stephenson demanded the radio, William Fleming Jr., a store employee, confronted her. Defending his mother who was being verbally abused, Stephenson began fighting Fleming and threw him through a window, injuring him. Stephenson and his mother were arrested and charged with disturbing the peace.

Both pleaded guilty and received a $50 fine. The Stephensons were arrested again after William Fleming Sr. filed charges against them on behalf of his son for assault with the intent to commit murder. Julius Blair, a local black businessman, posted the Stephensons’ bond and they were released.

During the same time, however, a white mob after hearing about the fight between Fleming and Stephenson, gathered at the Maury County Courthouse while black townspeople came together in Mink Side, a black business section. Concern about the fight and the possibility of mob violence against the entire black community prompted many of them to arm themselves. They decided to turn out the lights in Mink Slide and began shooting out the streetlights.

Hearing the gunshots, the Columbia Police Chief sent four patrolmen to Mink Side. When the police arrived, blacks blocked their entry. More shots rang out and the four officers were wounded. Following the shooting, Tennessee State Safety Commissioner Lynn Bomar led other police officers and state highway patrolmen into Mink Side. When they arrived, they began indiscriminately firing into buildings, searching homes, confiscating weapons, and, according to some, stealing residents’ property. During the confrontation, more than one hundred black women and men were arrested

On February 28, 1946, the Maury County deputies began questioning the prisoners about the shooting of the policemen. Three black men were singled out as most likely responsible: James Johnson, William Gordon, and Napoleon Stewart. During the interrogation, Tennessee highway patrolmen arrived and took the three men, whom they accused of shooting at them, to the sheriff’s office. Two of the prisoners, Johnson and Gordon, took weapons from the officers and began shooting at the other patrolmen. The patrolmen returned fire, killing both Johnson and Gordon and injuring one other prisoner. Stewart was not injured during the shooting.

The executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Walter White, and chief legal counsel Thurgood Marshall came to Columbia to organize a defense for the remaining prisoners. They brought in attorneys Z. Alexander Looby of Nashville and Maxwell Weaver of Chattanooga, for the upcoming trial.

Twenty-five Columbia blacks were tried on charges of shooting at white policemen in nearby Lawrenceburg, Tennessee. On October 4, 1946, an all-white jury surprisingly found only two of the twenty-five blacks guilty, and the charges were later dropped. One reason for the verdict: many whites in Lawrenceburg felt embarrassed that trial had to occur in Lawrenceburg instead of Columbia where the riot occurred. The Columbia Race Riot of 1946 foreshadowed the growing militancy of blacks that would be seen in the numerous urban uprisings of the 1960s.” from BlackPast

The Colfax Massacre in Louisiana (April 13, 1873)

More than 300 armed white men, including members of white supremacist organizations such as the Knights of White Camellia and the Ku Klux Klan, attacked the Courthouse building. When the militia maneuvered a cannon to fire on the Courthouse, some of the sixty Black defenders fled while others surrendered.

When the leader of the attackers, James Hadnot, was accidentally shot by one of his own men, the white militia responded by shooting the Black prisoners. Those who were wounded in the earlier battle, particularly Black militia members, were singled out for execution. The indiscriminate killing spread to African Americans who had not been at the courthouse and continued into the night. from BlackPast

Rosewood Massacre in Florida (Jan. 1, 1923)

A white posse formed on Jan. 1, spurred by the false accusation of a white married woman who claimed to have been beaten by an (unnamed) Black man. (Most likely to cover for the beating by her white lover.) The posse carried out lynchings of African Americans and burned the town to the ground. from the Zinn Education Project

Hamburg Massacre in South Carolina (July 8, 1876)

On July 4, 1876, (in the midst of a heated Reconstruction era local election season) a Black militia was engaged in military exercises when two white farmers attempted to drive through. Although the farmers got through the military formation after an initial argument, this event provided the excuse sought by whites to suppress Black voting through violence.

On July 6, in a courtroom, the farmers charged the militia with obstructing the road.

The case was postponed to July 8, by which time more than 100 white men from local counties had gathered in the town, armed with weapons. The African Americans attempted to flee, but 25 men were captured and six were murdered. from the Zinn Education Project

Orangeburg Massacre in South Carolina (1968)

The Orangeburg Massacre occurred on the night of February 8, 1968, when a civil rights protest at South Carolina State University (SC State) turned deadly after highway patrolmen opened fire on about 200 unarmed black student protestors. Three young men were shot and killed, and 28 people were wounded. The event became known as the Orangeburg Massacre and is one of the most violent episodes of the civil rights movement, yet it remains one of the least recognized. from History.com

To examine any book more closely at Amazon, please click on image of book.

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

p.s. Related posts:

When Mixed Race Marriage Was Illegal: What They Don’t Teach in History Books

Segregation in California Schools: What They Don’t Teach in History Books

The Chinese Exclusion Act – What They Don’t Teach in History Books

Civil Rights Movement Books for 4th Grade and MLK Day

5th Grade Slavery Unit in Newton

Visiting the exact location of the Boston Massacre: A Unit on the American Revolution

Top Children’s Books to Help You Address the Diversity of Human Race

Voting and Election Children’s Books

Books for Kids To Celebrate MLK Day

Enslaved Poet: Phillis Wheatley

Heroes of Black History: Rosa Parks #BlackHistoryMonth

HARLEM: Found Ways & Harlem Children’s Books

Civil Rights Movement through Art and Books for Kids

African American Books for Kids

Civil Rights Movement Book Lists for Kids

Civil Rights Movement Art #BlackLivesMatter

Civil Rights for Kids Picture Book of the Day

Picture Book of the Day: Booker T Washington

Celebrating Martin Luther King Jr. with 3 Children’s Books

Top 10: Best Children’s Books On Civil Rights Movement

Follow PragmaticMom’s board Multicultural Books for Kids on Pinterest.

Follow PragmaticMom’s board Children’s Book Activities on Pinterest.

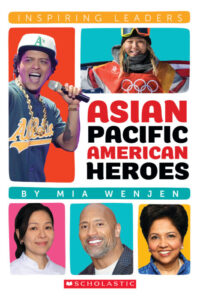

My books:

Food for the Future: Sustainable Farms Around the World

- Junior Library Guild Gold selection

- Selected as one of 100 Outstanding Picture Books of 2023 by dPICTUS and featured at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair

- Starred review from School Library Journal

- Chicago Library’s Best of the Best

- Imagination Soup’s 35 Best Nonfiction Books of 2023 for Kids

Amazon / Barefoot Books / Signed or Inscribed by Me

So much to learn! Thanks for such an informative and thoughtful post.